How long will it take to restore the Kawuneeche Valley to its former glory?

Organization and citizens band together to work on both public and private land

Isaac Elliot/Courtesy photo

Local and state organizations are banding together under a common goal: restoring the once biodiverse wetlands and forests of the Kawuneeche Valley. However, they know it will be a decades-long process.

“We’re doing this, basically, for our grandchildren,” said Geoff Elliot, founder of the restoration group Grand Environmental Services.

Elliot, his son Isaac and project collaborator Robin Doner spent a week in October planting trees on Kawuneeche Ranch, a privately-owned property that suffered significant landscape damage, including the burning of 99 percent of its trees, in the 2020 East Troublesome Fire.

His team is focused on reforestation in riparian-adjacent zones to boost ecological diversity. So far, they have planted 2,500 total trees in the area.

Over the next few years, planters will add more spruce, Ponderosa pine, Douglas fir and different shrubs such as tall willows to the burned valley. The goal in cultivating this land in the wake of East Troublesome, Elliot said, is creating a resilient, diverse forest that can protect itself from future blazes.

“What’s growing back after the fire is not diverse,” he said. “It’s all lodgepole pine coming up, and we know wildfires love a monoculture of trees.”

Multiple projects and partners look to mitigate wetland loss

Restoration at the Kawuneeche Ranch is one of several ongoing projects in the valley, with timelines ranging from five years to multiple decades. Elliot said the work he and Doner are doing on private land compliments the Kawuneeche Valley Restoration Collaborative‘s larger-scale wetland restoration on public lands in Rocky Mountain National Park, which focuses on reviving dwindling beaver populations.

The collaborative includes Rocky Mountain National Park, the U.S. Forest Service, Grand County, the town of Grand Lake, The Nature Conservancy, Rocky Mountain Conservancy and Northern Water. Formed in 2020, they were guided by research from Colorado State University documenting decades of ecological changes in the valley.

That research revealed a rapid ecological collapse, with a 94% loss of beaver ponds since 1953 and a 98% loss of tall willows since 1999.

“We’re not necessarily looking to bring beaver back, but we’re looking to restore the habitat that would entice beavers to come back,” said Kimberly Tekavec, a specialist at Northern Water and member of the collaborative.

To do this, teams are working to increase willow cover by installing fencing to reduce elk and moose browsing, planting native species to restore vegetation and building in-stream structures that mimic natural beaver activity. These structures help raise the streambed and water table, which supports healthier riparian growth, Tekavec said.

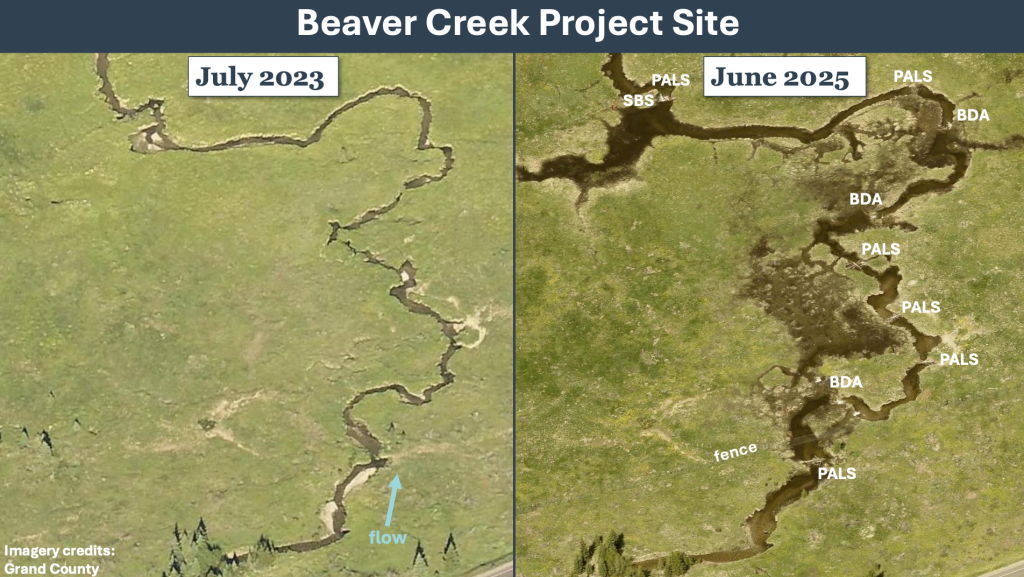

Beaver Creek is one of four sites in the valley along the Colorado River undergoing rehabilitation. The project covers 31 acres surrounded by a 10-foot-tall fence, designed with small openings at the base so smaller wildlife can pass through.

Within the project area, the restoration collective has installed 29 in-stream structures and carried out willow and alder plantings this September. They have also been treating the area for noxious weeds.

Like Elliot, Tekavec acknowledged the long-term initiative will take years of consistent effort to see widespread results. However, she saw notable increases in surface water from 2023 to 2025 in recent drone images, which she said is an overwhelmingly positive sign.

“It’s going to take some time to see really measurable changes,” she said, but collaborators have begun the process of measuring progress and tracking beaver numbers using wildlife cameras.

Organizations hope to bring private land owners on board

The group hopes to expand their endeavors to private lands in the future, starting with site assessments next spring while working to educate landowners about their project, Tekavec said.

Getting permission to work on private property often requires convincing landowners, Doner said, since the projects often depend on these owners’ financial contributions. As state and federal grant opportunities become even more limited, Doner said he and Elliot are dependent on private funding to carry out their expanded restoration plans.

“I want people to think about how to become a natural resource manager of their own property,” he said.

Reaching out to individuals and addressing audiences at organized speaker events helps to bring education to a broader scale so that landowners can understand why funding the work is important, he said.

As the effort to restore the Kawuneeche Valley grows, Doner said he hopes to bring in Grand County residents to strengthen the movement by fostering a stronger sense of land stewardship.

“I’ve been on landscapes for over 30 years,” he said. “Instead of having an informed scientific approach, I think maintaining a little more flexibility intellectually, functioning more from your heart and just listening — that works a lot better if you want to be a land steward.”

Similarly, Tekavec sees the project as an opportunity for collaboration across the state and nation, and said she hopes to be a model for other watersheds facing degradation from climate change.

“I hope we can be a test case,” she said. “We are monitoring plans and reports, learning as we go and adaptively managing so we can exemplify how this work can be done in other areas. We all may have different overarching goals, but we all agree that restoration of the valley is really critical.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

The Sky-Hi News strives to deliver powerful stories that spark emotion and focus on the place we live.

Over the past year, contributions from readers like you helped to fund some of our most important reporting, including coverage of the East Troublesome Fire.

If you value local journalism, consider making a contribution to our newsroom in support of the work we do.