New documentary seeks to raise awareness of Colorado’s murky river access laws

‘Common Waters’ delves into the tension between public and private access to Colorado waterways as momentum builds for a statewide remedy

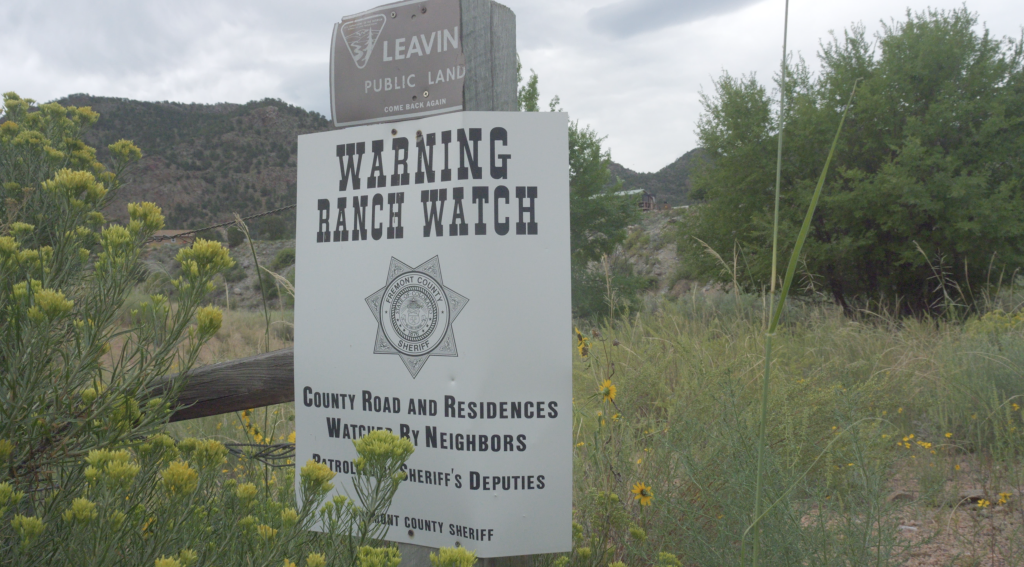

Cody Perry/Courtesy photo

Accessing rivers and streams is a “fundamental component of our culture and identity,” says an unnamed narrator in the opening minutes of a Colorado filmmaker’s latest short film.

Yet it is also “an enduring conflict.”

In his 20-minute documentary “Common Waters,” filmmaker Cody Perry puts a spotlight on Colorado’s murky river-access laws and how decades of ambiguity have led to public confusion.

Perry, an avid rafter and outdoor enthusiast, is the cofounder of Rig to Flip, a Colorado-based video company that focuses on stories about the Colorado River Basin. He’s also the chair of the recently-formed Colorado Stream Access Coalition, a group that advocates for the public’s right to recreate in waterways.

“As a boater, and specifically in Colorado, the concept of ‘adventure’ is something that’s quite universally held by everyone that’s into outdoor recreation,” Perry said. “We want to go out and experience the outdoors. We want to share those experiences with our friends and family. And so, in a large way, it defines our culture, and I’m not separate from that.”

“Common Waters” is a film two years in the making. Perry said the concept came about when he was approached by several outdoor conservation and recreation groups who were in the early stages of building a coalition to advocate for stream access.

The issue has a long and tumultuous history in Colorado, which has seen a host of legal battles over recreationists entering sections of waterways that overlap with private land. At the center of the debate is the question of when and whether the public has a right to use those segments of streams.

Perry said he first became aware of the issue following a high-profile dispute in 2009 between rafters and landowners along the Taylor River near Gunnison. A confrontation between the two parties snowballed into a legislative push a year later at the state Capitol to codify commercial rafters’ “right to float” through private property — a measure which ultimately failed.

Fifteen years later, the issue of stream access remains unresolved. Fearing that the debate has “faded into the background,” Perry said he hopes his film will both educate Coloradans on the unclear laws around river recreation and spur legislators to take decisive action.

“This is their job,” Perry said of state lawmakers. “They’re elected to this office to essentially figure out these hard issues for the public.”

A longstanding issue

Perry’s film highlights stories from river basins across the state and features interviews with recreationists, river advocates and policy experts.

Pro-access groups often base their argument for the public’s “right to float,” or, for anglers, the “right to wade,” on a section of the Colorado Constitution.

The state’s founding legal document says all natural streams, except those already appropriated under a water right, are owned by the state and dedicated to public use. A landmark 19th-century Supreme Court decision also affirmed that right in the U.S., saying that states, and, by extension, the public, own the bed of navigable rivers, meaning a waterway that is deep, wide, and calm enough for commercial or recreational use.

Yet Colorado has not defined which of its rivers are navigable and therefore open to public use, and legal precedent in the state has largely upheld property owners’ rights to bar access to private sections of streams. One of the most high-profile cases was in 1979, when the Colorado Supreme Court upheld the criminal trespassing conviction of a group of recreators who had floated into a private section of the Colorado River, even though they had entered from public land.

In “Common Waters,” environmental lawyer Mark Squillace said that the case “effectively made it illegal for people to float through private property,” adding that the court’s decision “has been kind of an albatross around our neck ever since.”

More recently, longtime Colorado angler Roger Hill sued a landowner who threw rocks at him for fishing in a privately-owned section of the Arkansas River near the Royal Gorge.

Squillace represented Hill in the case, arguing that streams that were navigable at statehood are public property. The state Supreme Court ultimately ruled against Hill in 2023, finding that Hill lacked legal standing.

“Common Waters” follows some of the aftermath of Hill’s case, with the octogenarian angler now flirting with being arrested for wading in a private stream, if it means being given the chance to bring a legal defense to court.

The film shows Hill entering segments of a river from public land and wading downstream until he finds an ideal fishing spot that could invite confirmation from landowners.

“Some people have said, ‘Are you engaging in civil disobedience?'” Squillace says in the film. “And I say, ‘No, we’re just asserting our right to do what we have a legal right to do, what we believe we have a legal right to do.'”

Perry said it’s important that river users understand the risk they may be putting themselves in when they recreate, adding that there’s a “false assumption” in the community that they can avoid legal issues so long as they don’t touch the riverbed.

Such issues will only persist until Colorado more clearly defines the public’s access to rrivers and streams, he said.

Colorado is an outlier in that regard. Other states in the West have more clearly defined and more consistently upheld public access to rivers and streams through court rulings, legislation, or both.

“Every other Western state has been able to address and figure out this issue,” Perry said.

Another push for legislation?

This summer, the stream access coalition that Perry chairs brought together several state lawmakers in Grand County for a rafting trip on the Colorado River, where they discussed the issue and the need for clearer stream access laws.

While Perry said the coalition remains focused on education and advocacy, it is not currently pursuing legislation itself.

Some river advocates are hoping to see a bill during the legislative session that begins in January that would codify some existing river access rights, which would be narrower in nature than what the coalition initially envisioned.

“We would like to see it be more broad, but, again, there’s nothing on the table at the moment,” Perry said. “When something is to come up, we would more than likely be supportive. But, we feel like our current focus right now is just especially doing a really strong ground game.”

If and when a bill does come before the legislature, it’s all but certain to ignite intense debate. The failed 2010 bill was closely watched by supporters and opponents, and drew hundreds to the Capitol for passionate, late-night testimony.

Landowners are likely to coalesce against a measure that seeks to loosen restrictions on private river access.

During a panel discussion on stream access with lawmakers in August, Garin Vorthmann, a lobbyist who has long represented the Colorado Farm Bureau, said she’s working with “a board coalition of agriculture interests, landowners, private businesses and realtors” who are concerned about private property rights.

“In Colorado, the law is established and clear that landowners who own the streambed have the right to exclude others from the property,” Vorthmann told lawmakers on the Water Resources and Agriculture Review Committee, which meets year-round to study and discuss conservation and water management issues.

Vorthmann warned that changing the status quo would “embroil the state in endless and expensive litigation,” adding that increased public access could degrade waterway health and increase liability risks for property owners.

A September study from the free-market think tank Common Sense Institute also lays out a case against legislation designating public streambeds and embankments. The study argues that doing so would violate the “Takings Clause” of the Colorado Constitution, which prohibits the government from taking or damaging private property without compensation.

The study argues the current system of case-by-case mediation between recreationists and landowners is “likely the best solution from a cost and legal standpoint.” It also says Colorado should collect more data on public and private waterways.

Perry said the issue of stream access is “complex and so fraught,” adding, “I don’t delude myself into thinking it’s going to be easy.”

Still, he’s hoping his film can help drive the conversation forward.

“Stories are a powerful medium. That’s where I come in,” Perry said. “… Film is a powerful construct for people to see issues, understand issues.”

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

The Sky-Hi News strives to deliver powerful stories that spark emotion and focus on the place we live.

Over the past year, contributions from readers like you helped to fund some of our most important reporting, including coverage of the East Troublesome Fire.

If you value local journalism, consider making a contribution to our newsroom in support of the work we do.