Field of dreams: Restoring Rocky Mountain National Park’s Kawuneeche Valley

Eric Brown/Northern Water

While casual visitors might not know it, Kawuneeche Valley on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park was once a winding, damp and biologically diverse wetland populated by an estimated 600 beavers. Today, the 15-mile-long valley looks more like a lush, grassy prairie. However, if explorers take a closer look at the ground beneath them, they’ll see clues from the past all around.

Kawuneeche Valley is only a few miles downstream from the headwaters of the Colorado River which begins at La Poudre Pass Lake in the high peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park and flows south through the valley. The river and its tributaries eventually pass through seven states and provide water to around 40 million people.

Historic photos taken from the 1880s through 2000 show that the Colorado River and its tributaries were once covered in a dense canopy of tall willows. In the Kawuneeche Valley, the wetland ecosystem was characterized by beavers, high water tables and aquatic vegetation. When the valley was a wetland, it carried out important ecological functions for wildlife habitat, flood control and resistance to wildfires and drought.

Wetlands can easily go unnoticed in Rocky Mountain National Park, since they make up only a small area of the park, but they do provide a multitude of benefits for the environment. Birds, moose and elk use wetlands for drinking water and rare, water-loving plants make their homes in wetlands – creating a hotspot of biodiversity.

Over time, an imbalance of local wildlife, geomorphic processes and the rise of ranching changed the landscape to the point where it has become unrecognizable. Today, the valley functions more like a elk-grassland ecosystem than a beaver-wetland one.

Visitors with a keen eye will notice an array of bumpy hills across the valley which are actually old relics of beaver dams. Sometimes within the dam relics, one will notice woody debris wedged into the dam by its previous tenants.

Scattered across the landscape are small willows that scientists call “zombie willows”, due to their ragged appearance. A closer look at the tree bases sometimes reveals angular cuts made by beavers of the past who cut down the willow stems for their dams. Examining these remnants of the past requires a person to slow down and look down, which can be hard when surrounded by towering Rocky Mountain peaks. It’s certainly worth the effort.

One group is working towards restoring the valley back to the lush wetland it once was. The Kawuneeche Vally Restoration Collaborative is a coalition that includes the National Park Service and numerous other partners who are actively working to bring back the beavers to Kawuneeche Valley. While the collaborative is kickstarting work in the valley through building dams, installing fencing and more, the members are hopeful that beavers will come in and finish the job.

How and why did the Kawuneeche Valley ecosystem change so drastically?

A lot of things have changed over the past 200 years, including human population increases, land management practices to create domestic livestock grazing and hay pastures, and major hydrologic modifications like Grand Ditch and the Colorado-Big Thompson Project that divert water from the Western Slope to the Front Range. This biome shift was only exacerbated by the 2020 East Troublesome Fire, the second-largest fire in the history of Colorado, and an increasingly arid Western climate.

The proliferation of invasive plant species such as Kentucky bluegrass, reed canary grass and Canada thistle also contributed significantly to the valley’s transition to a high-elevation grassland. But the biggest factor of all, perhaps, arrived at six-feet-tall with giant antlers.

In the 1970s, moose were introduced to Colorado from Wyoming and Utah. Not native to the area, they soon began thriving in Rocky Mountain National Park, partly due to a lack of predators. Willows are highly nutritious which makes them an important part of elk and moose diets. During the summer, willows comprise over 90% of the moose’s diet, and an adult male moose consumes an average of 45 pounds of willow daily, according to the National Park Service.

Heavy browsing by elk and moose led to the remarkable decline in willow height and cover. Beavers were unable to compete with the large ungulates for the willows they rely on for dam building and winter food caches. The rise in elk and moose populations over the next few decades decimated the willow population in the valley, which in turn led to the vanishing of beavers and their dams.

Isabel De Silva Shewell, an ecologist working for Rocky Mountain National Park, said that while it is hard to know exactly how many moose live in park today due to their solitary nature, surveys conducted by the park in 2019 and 2020 counted at least 150 moose living the park. De Silva Shewell said that the actual number of moose living in the park is likely higher.

The next arrival was Canis lupus, better know as the gray wolf. Wolves were eradicated in Colorado in the mid-1940s, but in 2020 voters voted to reintroduce wolves to the state. However, ecologists believe it’s unlikely that the reintroduced wolves will be a cure-all for controlling ungulate populations.

In September 2023, collaborators from Colorado State University and other universities published an ecosystem condition assessment report of the valley that analyzed nearly 70 years of aerial photos and climate records, as well as more than 20 years of hydrology and vegetation data. The study found that the area of beaver ponds has decreased an incredible 94% between 1953 to 2019, from 172 acres to 12 acres. It also found that beaver pond size had decreased significantly and that a substantial portion of this decline occurred after 1999. The loss of these beaver ponds and tall willows has likely led to the decline of amphibian and migratory bird populations in the area, according to the 2023 study.

Other documented changes in the Kawuneeche Valley include a 77% loss of tall willow acreage since 1999, elevated nitrogen and phosphorous concentrations in streamflow, as well as increases in invasive, non-native, dry land plant species at the expense of native wetland species.

Researchers involved in the 2023 study sounded the alarm about restoration and the Kawuneeche Valley. They believe that if nothing is done about the heavy browsing being done by moose and elk, more willows will perish in the coming decades. As time goes on, the potential for restoration will diminish as the cost of restoration increases.

The Kawuneeche Valley Restoration Collaborative appears on the scene

In 2020, a number of factors lined up which enabled the Kawuneeche Valley Restoration Collaborative to form. After years of conversations, the collaborative was finally able to find organizations willing to work on the project and help secure funding.

The collaborative receives support from a variety of partners including Northern Water, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado River District, Grand County, the town of Grand Lake, the United States Forest Service and The Nature Conservancy. A team from Colorado State University, who has worked for decades with the National Park Service to study ecosystems in Rocky Mountain National Park, also pitches in by performing assessments and recommending potential restoration sites.

Water quality specialist Kayli Foulk and water quality manager Katherine Morris, who both work for Grand County, are are actively involved in the restoration work. Grand Lake, Colorado’s deepest natural lake, has been experiencing spikes in nutrients which can lead to overgrowth of weeds, algae and sediment which can cause water quality degradation.

It’s more than an environmental issue, as thousands of visitors come to Grand County each year to recreate and small towns like Grand Lake depend on tourists for their economy vitality. By performing upstream restoration work in the Kawuneeche Valley, it’s possible to reduce the amount of nutrients and sediment entering Grand Lake.

“[Wetlands] help soak up pollutants, and sediments and things like that. So their function is extremely important because the wetlands end up taking up the pollutants first before it can get into our rivers and streams. It makes the rivers and streams much more clean,” Foulk said.

The group’s sense of urgency only grew following the East Troublesome Fire that scorched parts of Rocky Mountain National Park and Grand Lake in 2020.

“Wetlands provide a source of protection for against wildfire,” said De Silva Shewell. “That’s part of the reason why this work is so important.”

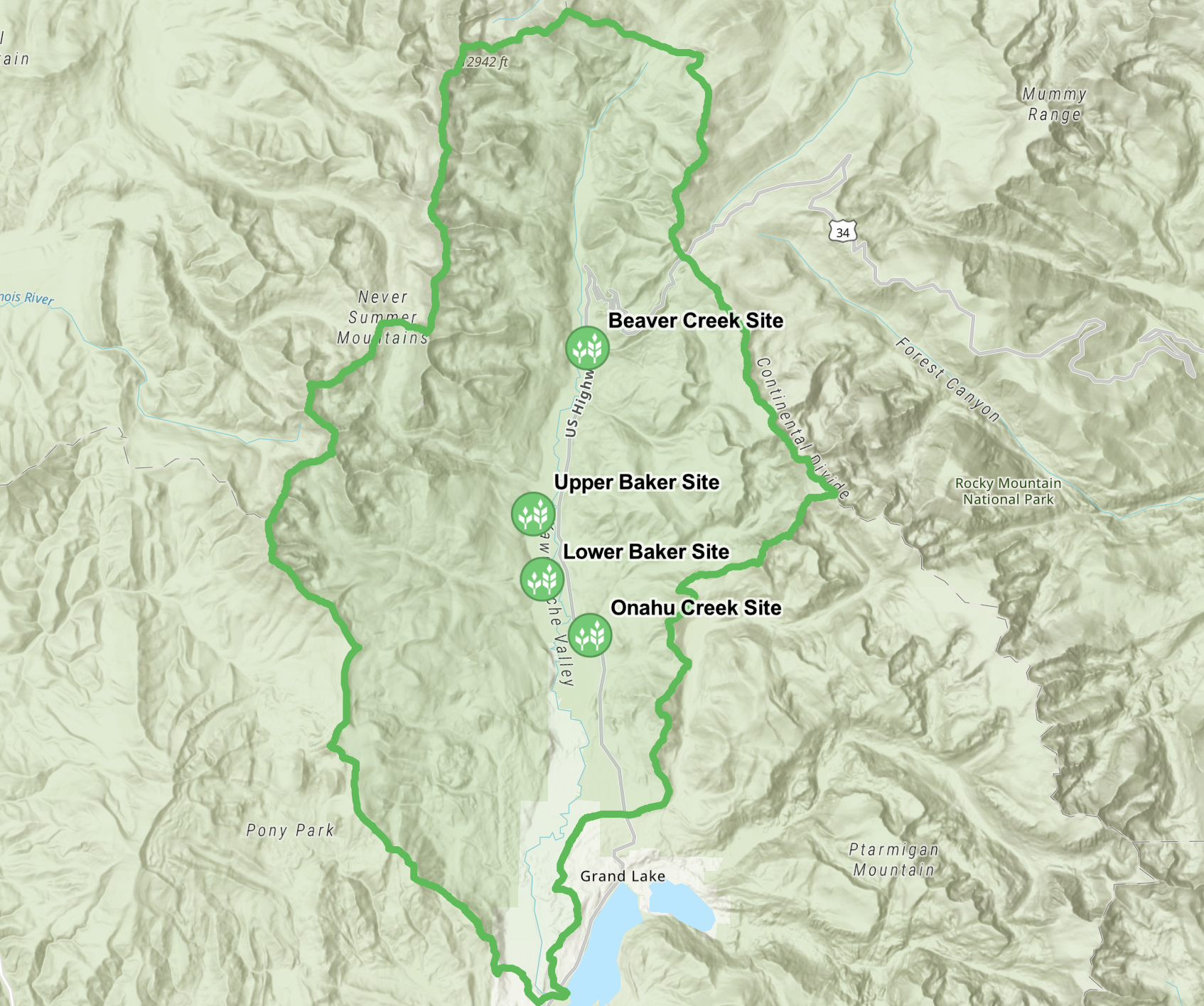

So far, the Kawuneeche Valley Resoration Collaborative has identified four sites within Rocky as being “highly suitable” for restoration.

What does restoring the Kawuneeche Valley look like?

Experts hope that by bringing beavers back to the landscape, North America’s largest rodents can pick up where they left off and return the valley to its wetland roots. Beavers were once numerous across the Kawuneeche Valley and historical beaver surveys estimate that there were up to 600 beavers living in the valley at one point.

Beavers are active in riparian areas all year long and live in large colonies consisting of several families. Colonies build large dome-shaped homes made of branches, sticks and mud, aptly called beaver lodges. They eat both woody and non-woody plants and store large qualities of aspen and willow for winter consumption.

Thanks to the impact of their dams on the landscape, beavers are regarded as a keystone species that modifies the environment in ways that benefit the ecosystem and encourage the presence of other species.

Bringing back beavers is crucial to properly restoring the Kawuneeche Valley, De Silva Shewell said. However, due to the current state of the Kawuneeche Valley, it’s highly unlikely beavers will return on their own.

As such, the collaborative is working to build beaver dam-like structures to give beavers the kick-start they need to draw them back into the valley. Other restoration work includes building exclosure fencing to protect vegetation, native vegetation planting, removal of non-native plant species, filling or blocking abandoned ditches and removing human-constructed earthen levees.

The exclosure fencing is meant to deter moose and elk, while beavers and other small critters can still enter in the area through a gap at the bottom of the fencing. This method allows the willow to grow without being overbrowsed by ungulates, thereby allowing for faster recovery.

While the fencing is meant to keep ungulates out, people can enter through gates and witness the restoration efforts for themselves, as long as they make sure to close the gate behind them.

“We definitely encourage people to utilize these areas. We just ask that they try to make sure the gates are set so we can have these continue to be an effective restoration tool that keep the moose and elk out,” De Silva Shewell said.

In 2023, the first restoration project began at Beaver Creek, a major tributary of the Colorado River, with the treatment of invasive plant species. Then in 2024, exclosure fencing was placed to keep moose and elk out of the area as well as construction on about 30 beaver mimicry structures. The collaborative plans to finish work on the Beaver Creek area in 2025 and to start work on another restoration area.

Foulk explained that the reason that Beaver Creek was chosen as the first site for restoration work was because it was the most accessible among the pilot project sites, making it easy to host educational tours and for visitors to see the restoration work being done.

As work is completed, scientists are also consistently monitoring and recording conditions to evaluate results and measure the success of these efforts. Beaver Creek is already seeing results, De Silva Shewell said.

Just a few weeks after installing different stream structures, Beaver Creek went from a trickle to over three feet of water ponding, even during a usually dry time of year. Members of the collaborative are especially excited for this year because this spring and summer will be the first time that the team truly gets to see how the new structures perform throughout natural seasonal cycles.

According to the collaborative, beavers are already traveling to the human-made structures and they hope to see more in the future. The group isn’t currently looking to directly bring more beavers to the area. Instead, they’re hoping that the beavers will arrive of their own accord.

However, if for some reason, the habitat is restored and beavers are still missing from the landscape, scientists will consider bringing in beavers from other areas, but De Silva Shewell said she feels “pretty confident” that beavers will find these sites and adopt them on their own.

The cost of doing restoration work

So far, an estimated $2 million has been spent on restoration efforts, while the entire project could cost as much as $10 million.

Kimberly Tekavec, a source water protection specialist with Northern Water, is a partner in the collaborative. She said that much of the grant funding that the collaborative receives goes towards planning and designing future project sites. Even though the construction that the collaborative is doing is relatively low-tech in nature, there is a large amount of planning that goes into every decision, and that’s where expenses can really add up.

“From doing compliance work, we have to do wetland delineation surveys [and] rare plant surveys. Those things take time, they take people, and that can cost a lot of money,” Tekavec said.

Visitors driving or walking near the Kawuneeche Valley will typically only see the implementation piece of the restoration project. They don’t get to see the lengthy behind-the-scenes work of planning and design that ensures projects are successful.

“Implementation is what everyone loves to fund. Implementation is like the big panda,” Foulk said. “Everyone loves to support the panda, but there’s so much behind what makes projects successful. I can’t stress enough the importance of good planning and design.”

Another big cost of the project is monitoring, both before and after projects are installed. Tekavec explained that there isn’t a lot of data available about the work that they are doing, so collaborative members are trying to quantify the benefits of these projects to inform future efforts in wetland conservancy.

What benefits would restoring the Kawuneeche Valley bring?

Ecologists say that restoring Kawuneeche Valley to a beaver-willow wetland will support a more functional ecosystem, enhance wildlife habitat, protect drinking water quality and filter out sediments clouding downstream lakes and reservoirs.

Wetlands as serve as natural fire lines, sometimes halting wildfires as well as providing refuge for wildlife during fires. Beaver researcher Emily Fairfax compared the difference between riparian vegetation greenness in areas with and without beaver damming during wildfire. The study looked at five large wildfires and found that beaver wetlands remained lush green refuges even when fires scorched forests.

Fairfax’s research looked into the effectiveness of beaver dams as a low-tech, small-cost strategy to build climate resiliency. Beaver ponds slow and store water that can be accessed by vegetation during dry periods, protecting riparian ecosystems from drought.

De Silva Shewell said that once the willows regrow, they will also shelter migratory birds such as Western flycatchers and yellow warblers, creating a potential new favorite spot for birders.

Nonetheless, even with the fencing in place for quicker restoration, it’s estimated that recovery of the willows will take around 20 years. For collaborative members, that timeline comes with mixed emotions.

“It’s really awesome to think that, like, we can look back in 20 years from now and, say, ‘Oh, we were there when this project started,'” Tekavec said.

Foulk explained that although it’s tough to be doing this work without immediate results, science is usually a waiting game.

“I think that maybe people in science are used to that. I don’t know. We don’t get often instant gratification,” Foulk said while chuckling. “You know, things take a really long time to transpire.”

De Silva Shewell’s monitoring work does provide hope. For example, she already has hard data showing that the willows are growing when protected from elk and moose, versus willows not located within the exclosure.

“I tend to focus on some of the details and just take heart in the progress we see there,” she said.

Kyle Patterson is the public affairs officer for Rocky Mountain National Park who has seen similar work succeed during her time at the park. After 23 years in the park, she’s witnessed firsthand what impact exclosure areas can have over time.

In the early 2000s, when elk were staying in the park over the winter, rather then migrating down to lower elevations, high-intensity browsing on willows and aspen became a real issue. An elk vegetation management plan implemented in 2008 has led to flora recovery as the elk began to migrate to lower elevations during the winter again.

“We we keep calling it the ‘Field of Dreams.’ They say that ‘If we build it, they’ll come,'” Tekavec said. “We know they’re in the area and if we can support their habitat, then hopefully they’ll come and take over the work that we’re doing.”

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2025 Explore Grand magazine.

The Rocky Mountain Conservancy will arrange volunteer opportunities in September where the public can help plant willows and shrubs.

People can also sign up for summer outreach tours to learn and see the Kawuneeche Valley restoration efforts for themselves.

These volunteer opportunities are still being finalized. To stay updated with volunteer opportunities, sign up for the Kawuneeche Valley Restoration Collaborative’s newsletter at KVCollab.org.

Support Local Journalism

Support Local Journalism

The Sky-Hi News strives to deliver powerful stories that spark emotion and focus on the place we live.

Over the past year, contributions from readers like you helped to fund some of our most important reporting, including coverage of the East Troublesome Fire.

If you value local journalism, consider making a contribution to our newsroom in support of the work we do.